| So far as I can learn, such a thing has scarce been for these thousand years before, as a son, father, grandfather, atavus, tritavus, preaching the Gospel, nay, the genuine Gospel, in a line." Thus wrote John Wesley to his brother Charles, thirty years after the date of organized Methodism, concerning their ancestry. He could have said with equal truth that his female ancestors were as distinguished as their husbands-his mother, grandmother, and great-grandmother being renowned for their gifts of genius, for their intense interest in ecclesiastical life, and for their suffering in obedience to conscience. The founder of Methodism was not fully acquainted with the particulars of his remarkable ancestry. But in those rare moments when even the busiest of men naturally inquire about their forefathers he was profoundly impressed that Providence had favored his own household in a singular way. The ancestral line of the Wesleys revealed the fact that the principles of intellectual, social, and religious nobility were developing and maturing into a new form of pentecostal evangelism. On the southwestern shore line of England is the county of Dorset, a part of which was called "West-Leas,"lea signifying a field or farm. In Somerset, adjoining Dorset, there was a place called Welswey, and before surnames were common we have Arthur of Welswey, or Arthur Wellsesley (Wellesley), and John West-leigh, and Henry West-ley. There were landowners in Somerset named Westley in the days of Alfred the Great, in the ninth century. Sir William de Wellesley was a member of Parliament in 1339. His second son, Sir Richard, became the head of the Wesleys in Ireland, from whom descended Arthur Wellesley, Duke of Wellington, the conqueror of Napoleon at Waterloo. We step out on firmer ground and get nearer home in stating that a grandson of Sir William, Sir Herbert, now called Westley, was the father of Bartholomew Westley, and great-grandfather of our own John Wesley. Bartholomew Westley was about seven years old when James I came to the throne. He entered Oxford as the first on the list of coming students bearing the name of Wesley. After completing the classical course he graduated in "physic," which was his means of livelihood for some years to come. In 1620, at the age of twenty-five, he married the daughter of Sir Henry Colley, of Castle Carberry, Kildare, Ireland, by whom he had one son named John. Having taken "holy orders," Bartholomew Westley became a Puritan clergyman in the Established Church. In 1640 he was appointed rector of Charmouth, on the English Channel. When the Puritan rectors were ejected by Charles Stuart after the Restoration of 1660 he lost his parish, but continued to preach as a Nonconformist pastor of a portion of his old parishioners. The Royalists stigmatized him as a "fanatic" and a "puny parson," because of his small stature, but he was much beloved by his flock, and much lamented at his death, in 1680, being then about eighty-five years old. John Westley, son of Bartholomew and Ann, was born in 1636, and was consecrated to the ministry in his infancy. He was educated at New Inn Hall, Oxford University, and was an exceptional student.

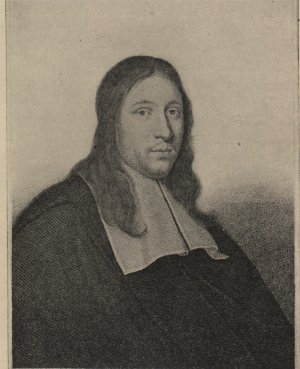

Samuel Wesley was born in 1662, in Dorsetshire, four months after the English St. Bartholomews Day, upon which his father and his grandfather were ejected from their livings for Nonconformity. His father dying when he was a lad, his education was cared for by his mother, and in 1678 some friends of his family sent him to a Nonconformist academy in London. Here he made the acquaintance of the eccentric bookseller and literary man, John Dunton, afterward the editor of the Athenian Gazette, a precursor of the Tatler and Spectator. Here also he obtained entry, as the son and grandson of distinguished confessors, into the best Nonconformist circles, of which one of the leading families was that of a Rev. Dr. Annesley. One of his schoolfellows was Daniel Defoe. He heard Stephen Charnock and John Bunyan preach, made notes of many sermons, and wrote some verses and unwise lampoons. He was about twenty years of age when he was asked to answer some strictures made upon the Dissenters, and while studying the subject he decided to leave Nonconformity and go over to the Established Church. With that quick impulse which distinguished all his subsequent life, he rose early one morning and started afoot for Oxford University, entering Exeter College as a servitor, with only two pounds and five shillings in his pocket.

At Oxford Samuel Wesleys character ripened. There was awakened in him a true pastoral feeling of compassion and responsibility by visiting the prisoners in the castle; as his sons did fifty years later, when he wrote to them, "Go on in Gods name in the path your Savior has directed and that track wherein your father has gone before you; for when I was an undergraduate at Oxford I visited them in the castle there, and reflect on it with great satisfaction to this day." As quaint old Fuller says, "Thus was the prison his first parish; his own charity his patron presenting him to it; and his work was all his wages." He took his degree of B. A. in i688, signing his name Wesley instead of Westley. He received his M. A. degree later from Corpus Christi College, Cambridge. Returning to London, he was ordained deacon by the time-serving but able Bishop of Rochester, Dr. Thomas Sprat, whom Dunton eulogized thus: His lucky hand made everything a flower. On earth the king of wits (they are but few), And, though a bishop, yet a preacher too! Twelve days after the Prince and Princess of Orange were proclaimed as King William III and Mary, Samuel Wesle) was ordained a priest of the Church of England by Bishoj Compton, of London, in St. Andrews Church, Holborn. Samuel Wesley became "passing rich" on £28 a year as London curate, then obtained a naval chaplaincy, commenced his metrical Life of Christ, and in 1689 married Dr. Annesleys accomplished daughter Susanna on another London curacy of £30 a year. The young couple commenced their married life in Holborn, in lodgings somewhere near the quaint old houses still standing opposite Grays Inn Road.

Annesley was tall and dignified, and of robust constitution. He had an aquiline nose, a short upper lip, wavy brown hair, and a strong and penetrating eye. Severe persecutions did not disturb the geniality and cheerfulness of his Christian life. When John Wesley had set the Churches of England aflame with the doctrine of Assurance he asked his mother whether her father had ever preached it. She replied that he personally enjoyed it and confessed it for many years, but did not recollect hearing him preach upon it in particular. She therefore presumed he regarded it as a high privilege of a few. How well he lived and died let these words witness: "Blessed be God! I have been faithful in the work of the ministry above fifty-five years." Shortly before his departure from this world, December 31, 1696, Dr. Annesley said "Come, my dearest Jesus! the nearer the more precious, the more welcome!" "I cannot express the thousandth part of the praise that is due to thee. I will die praising thee. . . . I shall be satisfied when I awake with thy likeness! Satisfied! Satisfied!" Dr. Williams, who founded the library now in Gordon Square, preached his funeral sermon, and exclaims: "0 how many places had sat in darkness, how many ministers had been starved, if Dr. Annesley had died thirty-four years since! The Gospel he ever forced into ignorant places, and was the chief instrument in the education as well as the subsistence of several ministers."

The second wife of this leading London divine was a daughter of John White, a member of the Long Parliament, and a man of the highest repute. She was a woman of rare accomplishments and remarkable piety. The youngest of her children, Susanna, who became the mother of John and Charles Wesley, was born on January 20, 1669, in Spital Yard, between Bishopsgate Street and Spital Square, London. Her home was probably in the last house, which blocks up the lower end of the yard. Here Susanna Annesley spent her girlhood, studied Church controversies, and asserted her personal decision, and hence she went forth to her wedding with Samuel 'Wesley. "How many children has Dr. Annesley?" inquired a friend of Thomas Manton, who had just baptized one of the family . "I believe it is two dozen, or a quarter of a hundred," was the startling reply. Susanna, the youngest, was perhaps the most gifted of the many beautiful and well-educated daughters. Her sister Judith was a very handsome and sturdy-minded woman, whose portrait was painted by Sir Peter Lely; Elizabeth, who married John Dun ton, was lovely in person and character, and Susanna shared largely in the family gift of beauty. She was slim and graceful, and retained her good looks and symmetry of figure to old age. The best authenticated portrait of her is one that was taken in her old age and engraved under the direction of her son John. It shows "delicate aquiline features, eyes still vivid and expressive under well-marked brows; a physiognomy at once benignant and expressive." Her letters reveal "a perfect mistress of English undefiled," some knowledge of 'French authors, and a logical mind well read in divinity. The secret of her deep spirituality is revealed in one of her letters to her son: "I will tell you what rule I observed in the same case, when I was young, and too much addicted to childish diversions, which was this-- never to spend more time in any matter of mere recreation in one day than I spent in private religious duties." Bishop McTyeires eloquent tribute to her virtues, graces, and gifts does no more than justice to this remarkable woman: "When I was in Milan I visited the church where Ambrose preached and where he was buried; but I thought more of his patroness, the pious Helena, than of him. I thought of Augustine, and of that mother whose prayers persevered for his salvation; and in the oldest town on the Rhine I could not help being interested in the legend of Ursula and her eleven thousand virgins. But greater than Helena, or Monica, or Ursula, there lived a woman in England, known to all Methodists, and of whom in the presence of those I have mentioned it might be said, 'Many daughters have done virtuously, but thou hast excelled them all. I mean the wife of the rector of Epworth, and the conscientious mother of his nineteen children; she that transmitted to her illustrious son her genius for learning, for order, for government, and I might almost say for godliness; who shaped him by her councils, sustained him by her prayers, and, in her old age, like the spirit of love and purity, presided over his modest household; and, when she was dying, said to her children, 'Children, as soon as the spirit leaves the body, gather round my bedside and sing a hymn of praise." Susanna Annesley, at the age of thirteen, was interested in the ecclesiastical and doctrinal controversies of the day. With remarkable independence she made up her mind to renounce Dissent and enter the Established Church, one year after Samuel Wesley had come to the same decision. It is possible that the two ecclesiastical conversions were not unconnected. Young Wesley was seven or eight years older than his future bride, and the friendship had already begun which was to ripen into love. In one of her later private meditations she mentions it among her greatest mercies that she was "married to a religious orthodox man; by him first drawn off from the Socinian heresy." The same feeling is expressed in the words of the epitaph from her pen inscribed on Samuel Wesleys tomb at Epworth: "As he lived, so he died, in the true Catholic faith of the Holy Trinity in Unity; and that Jesus Christ is God Incarnate, and the only Savior of mankind." It was natural that the thoughtful, fervent girl should be strongly influenced by one by whom she had been settled in a belief of such vital importance. "If the Puritans," says Dr. Rigg, "could not transmit to her lover and herself their ecclesiastical principles, at least they transmitted a bold independence of judgment and of conduct." The girl of thirteen expressed her opinions against the Church of her distinguished father, however, with such tact and sweetness of spirit as to win his consent to her confirmation at St. Pauls. She was at once so decided and gentle, and he so tolerant, that the love between the father and daughter never lost its strength and charm.

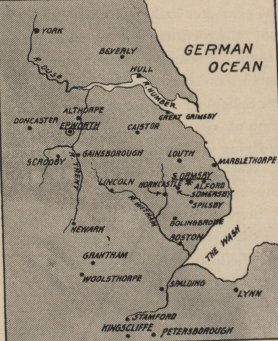

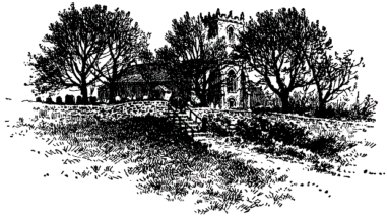

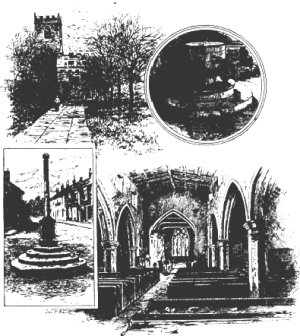

"The Puritan movement in which she had been reared," says Buoy, "went with her into the Church of England. She entered it essentially a Puritan, and that stern, heroic faith, softened by the grace of God, held her all her life. There was a providence leading this woman back to Anglicanism as plain as that which led the mother of Moses back to the court of Egypt, and she, like Jochebed, had her ministry-to train a child who should set the people free." "The Wesleys mother," says Isaac Taylor, "was the mother of Methodism in a religious and moral sense; for her courage, her submissiveness to authority, the high tone of her mind, its independence and its self-control, the warmth of her devotional feelings, and the practical direction given to them, came up, and were visibly repeated in the character and conduct of her sons." We left the young curate and his wife in their lodgings in London, where they "boarded without going into debt." Here their son Samuel was born, who became the poet and satirist of Westminster School and master of Tiverton Grammar School. In the autumn of 1690 the Marquis of Normanby presented Wesley to the living of South Ormsby, in Lincolnshire, worth £50 a year. Wesley himself describes the parsonage as "a mean cot, composed of reeds and clay." His family increased ''one additional child per annum." Again his pen came to the rescue, and Wesley published his Life of Christ, dedicating it to Queen Mary. At South Ormsby Wesley also published his treatise on the Hebrew points. Here also he wrote much for "The Athenian Gazette; or Casuistical Mercury, resolving all the nice and curious questions proposed by the ingenious." One third of the Gazette at this time was from Wesleys pen. About the beginning of 1697 Samuel Wesley was presented to the living of Epworth, in Lincolnshire, "in accordance with some wish or promise of the late queen;" here he continued for thirty-eight years, and here John Wesley was born on June 17, 1703, 0. S., the fifteenth of the rectors nineteen children. John Benjamin appears to have been his full name when christened, but he never used the middle name or initial. LINCOLNSHIRE, the county of "fen, marsh, and wood," has, perhaps, been the most assertive of all the seething counties of the eastern coast of the British Isles. In almost every great crisis of English history we find leaders from Lincoinshire. For at least seven hundred years it has been represented in the high places of English life by some illustrious son. The old market town of Epworth stands on a piece of land once inclosed by five rivers, and called the Isle of Axholme. Its population remains about the same as in the days of the Wesleys, when the parishioners numbered two thousand. They live, for the most part, in the one street that stretches out for two miles From the time of Charles I down to the first quarter of the eighteenth century the "stilt walkers" had fiercely resisted every effort to drain the fens, and when the work was accomplished by new settlers the older Fenmen burned the crops, killed the eattle, and flooded the lands of the intruders. The turbulent spirit of the Fenmen lingered still among the villagers of Epworth, who were also profligate and vicious in their habits--as Samuel Wesley discovered to his cost during his first twelve years among them. The exterior of Epworth Church remains much the same as in Wesleys day. Porches, walls, buttresses, and towers have not been materially altered in the two centuries. Within, the pews, organ, and decorations are new, the rood screen has been removed, the aisles have been reroofed, and six bells have been hung in the tower.

Let us take a look into the interior of the Epworth rectory, for in this household we have, as Stevens well says, the "real origin" of Methodism. Mrs. Wesleys education in the splendid religious environment of the twenty years life in her fathers house in London, and her diligent self-improvement during her married life, gave superior qualifications for the training of the school in the home. The method of living and the course of study have been given in a letter by the matchless teacher herself. The children were always put into a regular method of living, in such things as they were capable, from their birth; as in dressing, undressing, and changing their linen. When turned a year old they were taught to fear the rod, and to cry softly. "I insist," she says, "in conquering the will of children betimes, because this is the only strong and rational foundation of a religious education, without which both precept and example will be ineffectual, but when this is thoroughly done then is a child capable of being governed by the reason and piety of its parents, till its own understanding comes to maturity, and the principles of religion have taken root in the mind." As soon as the child learned to talk, its first act on rising and its last act before retiring were to say the Lords prayer, to which, as it grew bigger, were added short prayers for parents, some collects, a short catechism, and some portion of Scripture, as memory could bear. That genius of successful management which utilizes every help and helper was shown when, at the regularly designated hour, the oldest took the youngest that could speak, and the second the next, to whom were read the psalms for the day and a chapter in the New Testament. In the morning they were directed to read the psalms and a chapter in the Old Testament. They were taught to be still at family prayers, and to ask a blessing, which they did by signs before they could speak. The exquisite manners of John Wesley came largely from his careful training in childhood. The children were trained to''civil behavior;" saluting one another by the proper name with the addition of "brother" or "sister," yet nearly every child had a gentle nickname. Each must "speak handsomely for what was wanted," even to the humblest servant, saying, "Pray, give me such a thing." Telling the truth brought reward; rude, ill-bred talk was unheard; and the children were forbidden freedom with the servants in conversation or association, lest something coarse or evil might be projected into their lives. But there was recreation in abundance. They thus grew up in that humble home a healthy, happy, witty band of children.

"Why do you go over the same thing with that child the twentieth time? "said the rector impatiently to his wife. Because, said she, "nineteen times were not sufficient. It I had stopped after telling him nineteen times, all my labor would have been lost." There was even a successful adaptation of university study and method. Mrs. Wesley taught first by talks or lectures, then by text-books, and required essays or papers from the elder scholars. The classics were exalted, and the daughters took the same lessons as their brothers. Mehetabel, the first one trained by the systematic plan finally adopted, could read in the Greek Testament when only eight years old. The rector rendered assistance in the classics. In the school hours attention was given to the culture of the soul, and there even was a catechism drill in the primary department, and the teaching of Christian doctrines in the higher grades. Then there were Mrs. Wesleys own compositions, so highly commended by Adam Clarke, but lost when the rectory was burned. There were elaborate essays on religious and educational themes which she had prepared as text-books for her home school.

It was not all sunshine, however, in the Epworth home. The rector grew vexed because his wife would not respond "amen" to his prayer for the king. "Sukey, if we serve two kings, we must have two beds," and, as impulsively as when he left London for Oxford, Samuel Wesley hurried away to the London Convocation, to return only at the death of the king as if nothing unpleasant had ever occurred. There were many conflicts between the rash rector and his ungodly parishioners. They hated him, and he knew not how to win their love. Debts crowded in upon him. In 1705, when John was two years old, his father was arrested in the churchyard for a debt of £30 and hurried off to jail. His good wife sent him her rings to sell, but he returned them, believing the Lord would provide otherwise. We see him at work among his "fellowjailbirds" in Lincoln Castle reading prayers and preaching even securing books to distribute among the prisoners. He writes: "I am now at rest. I am come to the haven where Ive long expected to be." And again: "A jail is a paradise in comparison of the life I led before I came hither. No man has worked truer for bread than I have done, and few have lived harder, or their families either." But the storm beat more fiercely upon the rectory, for food was hard to find, the crop of the previous year having been a failure. The angry neighbors now burned the flax, stabbed the three cows that had given milk to the family, and wished "the little devils "the children in the rectory-would be turned out to starve. The delicate, brave-hearted wife toiled on, and kept together the half-fed and half-clothed children. "Tell me, Mrs. Wesley," said the Archbishop of York, "whether you have ever really wanted bread." "I will freely own to your grace," she replied, "that, strictly speaking, I never did want bread. But then I had so much care to get it before it was eat and to pay for it afterward as have often made it unpleasant to me; and I think to have bread on such terms is the next degree of wretchedness to having none at all." Friends came to the relief of the rector, and through the influence of the Duke of Buckingham he was presented with £125. After three months imprisonment he returned to his parish and his books. Then came the enemys torch. The rectory went down in ashes, and only the good providence of God saved the lives of John and his mother. It was on Wednesday night, the 9th of February, 1709. Mrs. Wesley was ill in her room, with her two eldest daughters as companions. Bettie, the maid, and five younger children were in the nursery, while Hettie was alone in the small bedroom next to the granary, where the newly threshed wheat and corn were stored. The rector left his study at half-past ten, locked the room that contained his precious manuscripts and the records of the family and parish, and retired to rest in a room near to his wife. It was a wild night. A howling northeast storm obscured the half moon. The fire crept up the straw roof and dropped upon the bed where Hetty slept. scorched and alarmed, she ran to her fathers room, while voices on the street cried, "Fire! fire!" The father warned his wife and daughters, helped them down stairs, and wakened those in the nursery. Bettie escaped with Charles in her arms, while three children followed. The brave father helped them into the yard and over the garden wall, and back to the house he rushed, trying in vain to find his wife. He tried to reach the study and failed. A dismal cry came out from the flames, "Help me!" "Jacky" had awakened to find the ceiling of his room on fire. The distracted father tried to force himself up the stairs, but streams of flame beat him back. He and the children committed the boys soul to God. Within, Mrs. Wesley, lost in the excitement, sought the opened front doors, but was forced, back by the blinding sheet of fire and smoke. At a third effort she was literally blown down by the flames. Calmly she sought divine help. Wrapped in a cloak about her chest, she waded knee-deep through the flames to the door. Her limbs were scorched, and her face was black with smoke, so that when found by her frantic husband he did not know her.

John, not yet six years old, climbed on a chest to the window, and cried to be taken out. One man was helped up over the shoulders of another, and the child leaped into his arms. At the same moment the roof fell in. The boy was put into his mothers arms. The rector, in his search for his wife, found her holding the child, who by this time he had thought was burned to ashes. He could not believe his eyes until several times he had kissed the boy. Mrs. Wesley said to him, "Are your books safe?" "Let them go," he replied, "now that you and all the children are preserved." He called on those near him to praise God, saying, "Come, neighbors, let us kneel down; let us give thanks to God. He has given me all my eight children. Let the house go; I am rich enough." To John Wesley for more than fourscore years this event was the initial of his vivid reminiscences. There was no place found in his thought from that time onward for a doubt of a Supreme Being whose mercy interposes in moments of danger. The mothers escape was as miraculous as that of her celebrated son. In later years he caused a vignette to be engraved of a burning house, beneath his portrait, and these words underscored: "Is not this a brand plucked from the burning?" The rectory was soon rebuilt in a more substantial manner and on a more commodious plan. While the rector is attending the Convocation in London the good mother holds service with her children on Sabbath afternoons in the kitchen, reading good books and sermons. Neighbors ask the privilege of coming to hear, and there are soon as many as thirty attending regularly. The rector, though displeased with the news, is delighted with the plan on his return. The next year he has a conceited curate, who writes him words of bitter complaint against the sermon-reading wife. She tells her husband of the good work, and that as many as two hundred come to hear. The curate writes him strong words of a "conventicle "--a pestiferous gathering of Dissenters-and the rector in reply urges his wife to discontinue the meetings. The defense of the mother of Methodism is in these noble words:

The marvelous service continued to shed its light abroad for who could resist the words and work of that matchless heroine of the spacious Epworth kitchen?

In two of his many enterprises in the press and the pulpit the vigorous rector notably

anticipated the principles of his Methodist sons; lie was the apologist of the ''religious societies" of his day, and lie was the advocate of "a broad and comprehensive scheme" of foreign missions. Indeed, he was to the year of his death `disposed, could the way be made clear, to go out himself as a missionary to heathen lands.

|