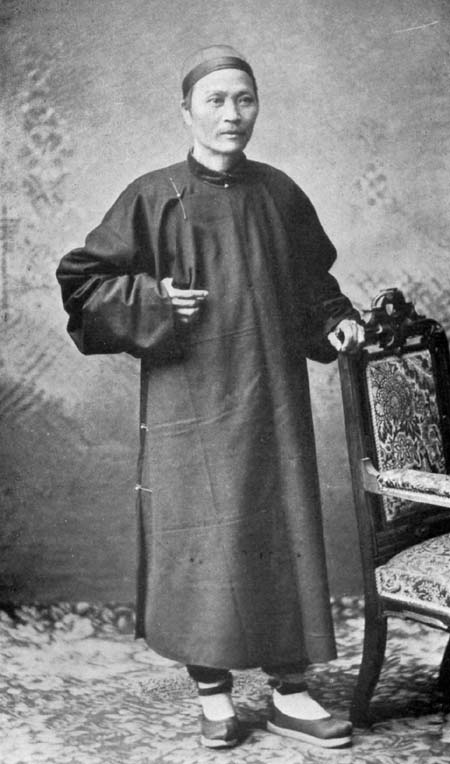

China and its culture have always seemed strange to Western-style thinking. Yet they need Christ as much as anyone else. This is a review of the struggle to give China the Gospel of Christ. Though the door is not completely open, there is a renewed hope of continuing the effort to evangelize this great nation and bring its people to our Lord. At one time, Methodism was second to none in championing the cause of Christ. This essay also honors those Methodist missionaries who labored for Christ in China. Since Richard Nixon visited China the world has seen many changes. China, like Russia, seemed hardened to the infiltration of the Gospel of Christ. However, now that the Iron Curtain has rusted away, Russia has been the center of a great struggle to present Christ. Many Russian people are reaching out and seeking the Lord. A country who boasted of their Atheism ten years ago is now seeing the love of Christ grow ever larger in their native land. China also has emerged from their Bamboo Curtain, and the Gospel of Christ has greatly expanded in spite of the communists' opposition. Nevertheless, the struggle to give China Christ has been an ongoing one for a long time and by many different people. In this paper I will trace the history of Christianity in that country. This is a survey of missionary work in China, and not an endorsement of groups that do not believe the Scriptures. The final focus will be on the missionary labors that the Methodists accomplished in that realm. We should note at the outset that the early Methodists preached the Gospel of Christ. By the time Communism took the nation, many were hedging on a "social Gospel." Nevertheless, many Methodists still believed the Bible and preached it faithfully. Many Bible believing Methodists gave their lives during the many communist purges. These Methodist Christians and others are to be honored over their brethren. May God bless the Bible believing Christians in that country. The effort to evangelize China with Christianity had its beginning in the seventh century with the Nestorians. After these followed several groups, who attempted to spread Catholicism throughout the land. These met with some success, but their influence was, for the most part, short lived. Then, in the nineteenth century, came the Protestant missionaries. We can attribute their success to God's moving in many political, economic and military events that occurred during this time. However, we need a short history of Christian missionary work before this era as background. Two major groups made some important advances in propagating Christianity before the Protestants arrived. The Nestorians(1) were the first to move through China with the gospel of Christianity. The first written record of them dates their appearance before Emperor Tai-tsung of the T'ang dynasty, as the twelfth month of Ching-Kuan A.D. 638. This religious group, which was lead by a man whose name in Chinese was O-lo-pen, was well received by the court.Historians have been unable to trace the identity of O-lo-pen back any farther, but we know that he was a disciple of Nestorius. Nestorius, Bishop of Constantinople during the years A.D. 428-431, refused the Catholic doctrine concerning the Virgin Mary, whom the Catholic clergy were fond of calling the "Mother of God." Nestorius found this objectionable because it implied she was the mother of the divine nature, an idea he denied. For this, the Roman Catholic Pope labeled him a heretic and he was later accused of rejecting the divinity of Christ. Although the controversy became very difficult, Nestorius and his followers did not withdraw from the organized church. This was the first Christian missionary activity to penetrate the wall of Chinese civilization.(2) O-lo-pen was the first man to teach the doctrine of Christ to the Chinese. Emperor T'ai-tsung received O-lo-pen and the doctrines he brought as a friend and encouraged the missionary work. A stone table, which was found in 1623 by some Chinese building a house, provided the facts about O-lo-pen's visit. A Jesuit priest by the name of Father Trigualt immediately recognized its importance. However, it was not until about 1800 that scholars accepted its authenticity. In part the stone table said: "When T'ai-tsung, the glorious emperor, began his happy reign in fame and splendor, illuminating and wisely ruling his people, there lived in the land of Tach'in a man of great virtue, O-lo-en by name, who, sooth saying from gleaming clouds, brought hither the holy scripture and overcame difficulties and dangers by observing the harmony of the winds. In the ninth year Cheng-kuan came to Chang-an. The Emperor sent his Minister of State Fang Hsuan-ling at the head of an escort into the western suburb, to receive the visitor and conduct him. His scriptures were translated in the library. When the doctrines were examined in the private rooms, the Emperor recognized their correctness of truth and ordered that they should be preached and disseminated." So it was, according to the passage quoted from the stone table, that the Emperor approved Christianity being taught to the Chinese people by the visitor, O-lo-pen. The stone table went on to say: "The Way has no unchangeable name. For the wise man no method is permanent. Doctrines exist to benefit the nation, and to protect the living. The Persian Monk O-lo-pen has come from afar with writings and doctrines to offer them in Shang-Ching. The meaning of the doctrines has been carefully examined. They are full of mystery, wonder and peace. They set forth the reality of life and of perfection. They signify the salvation and wealth of men. It is good that they should be disseminated about the Empire. To this end the local authorities are commanded to build a monastery for twenty-one monks in the I-ning district."(4) Although the Christian doctrine had received a fine reception initially, two political upheavals greatly slowed its spread. The first upheaval was the Arabian attack from the Sinai desert on the Byzantium Empire. The resulting victory for the Arabians at the battle of Yarmuk severely limited the growth of Christianity. It also hampered the work of O-lo-pen because they cut his line of communication with the church in Constantinople. The second upheaval that adversely affected Christianity in China was the change that occurred with the fall of the T'ang dynasty. Nevertheless, Nestorian Christianity flourished for about 200 years from A.D. 638 until 845.(5) The next time an outside Christian influence was felt was about 1265, with the visit of Nicolo and Matteo Polo. Although the Polo brothers' main interest in visiting the "City of Khan," Peking,(6) was as explorers, Kublai Khan extended a gracious welcome to them. He expressed great interest in their Christian beliefs, questioning them in detail about the Christian faith and western churches. Khan sent the two Venetians as envoys to the Pope in Rome requesting a hundred missionaries and oil for the lamp of the Holy Sepulchre. However, when the Polos reached Rome in 1269, they found the chair of St. Peter unoccupied. According to the records, they waited two years in vain for a new Pope. Upon their return to the land of Cathay, as they then knew China, Nicolo took his seventeen-year-old son Marco Polo, who later become a famous explorer.(7)About two years after the Polos left China for home, the Emperor Khan's dynasty collapsed. When the new Emperor, Hung Wu, and the Ming Dynasty were established, they outlawed Christianity and the influence it had on the Chinese people. So, in spite of the Polos, China again stood aloof from the rest of the world. China remained at arms' length from medieval Europe for more than three hundred years, until, in 1601, a Roman Catholic priest arrived in China. Matteo Ricci, a Jesuit, first met Chinese in Macao, in the southern part of China. Ricci's desire or motto was to be "all things to all men," and because of this, he compromised the Roman Catholic dogma by allowing ancestor worship and other pagan rites.(8) After several years of hardship, Ricci made his way to Peking. Ricci so impressed the Chinese government with his knowledge of geography, mathematics, and astronomy that he secured employment in the government. Before his death in 1610, Ricci saw many important Chinese officials, including an imperial prince, converted to Catholicism.(9) Another Jesuit priest, Johann Adam Von Bell Scholl, known in Chinese history as Father Scholl, followed Matteo Ricci in Peking. He also was "invited to the imperial court at Peking, where he became royal astronomer and scientific advisor to the emperor and was entrusted with reforming and compiling the Chinese calender."(10) Scholl gained the Emperor's favor and was allowed to spread his faith and build churches. Nevertheless, the influence of Ricci and Scholl was short lived, primarily because their compromises caused conflicts among the church leaders in Rome and resulted in hard feelings toward the Chinese. It was during this conflict that the Roman Catholic Church fell out of favor with the Chinese Emperor. In 1724 all Christians and Christianity were banned from the country and the property of the Roman Catholic Church was confiscated.(11) The years between 1724 and the beginning of the nineteenth century saw only scattered underground efforts to evangelize. In the early eighteen hundred's, China saw the first real activities of the Protestant missionaries, who came because of the opening of trade between China and other countries. This opening of trade was partially forced on a reluctant China by western nations. The British, French, Germans, and the Dutch each sought to advance their burgeoning economies by establishing trade with China. Even China's neighbor, Japan, soon was bidding for a part in the economic awakening of the sleeping giant Panda, China. China resisted the advances of the foreign traders, viewing, it seems, Western people as barbarians. The Chinese did not care to trade with the Western nations or even have diplomatic intercourse. Three different times the British sent different ambassadors to China, only to be rebuffed. The Chinese government showed its attitude to the first British envoy, Earl MaCartney, in the "You, Oh King" letter that they gave him to take to the British monarch. In essence, it said that China had everything she needed and the West had nothing to offer, so "stay away."(12) This isolationist's attitude proved a deadly political plaque to the Chinese government throughout the rest of the 1800's. They continually tried to keep the West out. A possible explanation for this Chinese attitude could be found in their two thousand years of Confucianism. The philosophy of Confucius affected all areas of Chinese life: religious, social, economic and political. In the political and economic areas, it supported the Chinese policy of self sufficiency and separation, and in the religious area it worked against the spread of Christianity. Confucianism is based on the teachings of Confucius, a man who lived from 551 to 419 B.C. According to the World Book Encyclopedia, Confucius worked his way up from a poor level to a scholarly position in the Chinese government. A conflict later developed between Confucius and some other members of the government. Because of this conflict, he retired in disgust. Some of his pupils, which were numbered at more than three thousand at the time, were considered among the sages in the Chinese Empire. After his death, some pupils gathered Confucius' sayings into a book "which for ages has been a textbook in every Chinese school."(13) During his life Confucius did a great deal of editing and compiling of Chinese classics, as well as his own compendium of Chinese history covering about 240 years, including his own lifetime. The philosophy of Confucius was to Chinese life much as the Constitution of the United States is to Americans. Dr. Williams, President of the London Missionary Society, says that Confucianism "contains the seeds of all things that are valuable in the estimation of the Chinese. It is at once the foundation of their political system, their history and their religious rites, the basis of their tactics, music and astronomy."(14) The teaching of Confucius includes the "Five Virtues" which are benevolence, righteousness, propriety, wisdom, and sincerity. This religion also contains the "Five Relations" of prince and minister, husband and wife, father and son, brother to brother, and friend to friend.(15) Both ideas expressed in the Five Virtues and the Five Relations are very close to Christian teaching. Christianity and Confucianism teach much the same principles concerning the treatment of one's fellow man. For example, Confucius said, "What you do not like done to yourself, do not unto others."(16) In his teaching, Christ said, "Do unto others as you would have them do unto you."(17) This similarity of ideas hampered the acceptance of Christianity because the Chinese followers of Confucianism felt they were as morally upright as the Christians. Confucius, however, could not offer them salvation, for in his religion there was no atonement for sins. Christianity, on the other hand, is based on the teaching that all men are sinners who need salvation, which they can only obtain through the blood atonement of Christ. This was difficult for the Chinese people to believe, much like our positive self esteem generation of today. The other religion of dominance in China at the time was Buddhism, which had come from India. Buddhism was established by a man called Buddha, who lived from 557 until 477 B.C. Buddhism teaches the incarnation of the soul. Each life is supposed to be devoted to works of holiness and spent in unceasing efforts to gain Nirvana. Toward this goal, Buddhism taught that one must follow the "Eightfold Path: Right belief, right resolve, right word, right act, right life, right effort, right thinking, right meditation."(18) Christianity and Buddhism can be contrasted on several points. The major divergences of both religions reflect the differences in their founders' lives. "The tragedy and the majesty of the Christ is very different from the peacefulness and sweetness of Buddha. Jesus sought to save the world, not himself. Buddha began by saving himself and then taught the world. The aim of Jesus is faith and individual existence in heaven in the presence of God: the summum bonum of Buddha is knowledge and the annihilation of self in Nirvana."(19) This was the historical tapestry of China at the turn of the nineteenth century, when the Protestant missionaries had to face Confucianism, Buddhism and anti-Western feelings in their struggle to reach China for Christ. Although China did not welcome the foreigners with open arms, their influence was there to stay. To lessen this influence, the Chinese began to put restrictions on the trade and movement of the Westerners. They developed a set of limitations that became known as the Canton system, because Canton was the only city in which they allowed the Westerners to trade. One injustice of the Canton system, according to Dr. Chia, a graduate of Political Science of Pennsylvania State University, was that unwritten tax rates allowed Chinese merchants to charge any amount they chose on incoming and outgoing goods. The Chinese government in the Canton system also imposed five restrictions on Western merchants. The first restriction limited the trading season, which only allowed foreigners to visit Canton from October to January. The second limitation forbad bringing Western women to Canton. No firearms, the third restriction, could be carried. The Chinese' fourth restriction made it illegal for foreigners to use the sedan chair. The last restriction forbid foreigners from learning the Chinese language.(20) In fact, any Chinese who willingly taught a foreigner the language could be punished by death. Western countries felt the system to be very unfair and set out to see it changed. It was during this time that the English Protestants began to organize and send out missionaries to foreign countries. The two most famous missionary societies of that time were the London Missionary Society and the Wesleyan Methodist Mission Society. Both soon became involved in evangelizing China. The first English missionary to labor on Chinese soil was Robert Morrison in 1807. Rev. Morrison arrived in Canton under the sponsorship of the London Missionary Society. The Canton system and imperial edicts against Christianity hampered his work among the Chinese. These problems forced Morrison to restrict "himself largely to, the preparation of literature. He had little liberty, living in a cellar and appearing only rarely in public. Morrison spent much time studying Chinese literature and language and won a job as an interpreter with the British East India Company. A translation of the entire Bible was completed by Morrison in 1819. He then went on to translate the Shorter Catechism of the Church of Scotland, part of the Church of England's Book of Common Prayer, pamphlets on the Christian faith as well as compiling a Chinese English dictionary and a grammar."(21) Morrison felt that improving Anglo-Chinese relations was important. To do this, he urged Cambridge and Oxford Universities, the leading institutions of higher education in England at the time, to establish Chairs of Chinese. He even offered to present his Chinese library to England. All of his efforts, however, were rejected by the politicians of the time. (22) England, it seems, missed an opportunity better to understand the Oriental people and affect China's development in a peaceful way. China's actions somewhat justified the English feelings. Lacy wrote, "Even the king of the greatest western empire was snubbed when his representative... had been refused an audience with the emperor or his officials in Peking, and Lord Napier's letter had been returned though the brokers at Canton because it was not inscribed as a humble petition."(23) Between 1810 and 1844 the foreign traders began marketing a product that won great popularity among the Chinese. They began to sell opium. They knew the opium poppy in China as long ago as the T'ang dynasty (A.D. 618-906), and they have produced opium there for more than four hundred years. Although it was not smoked much, if at all, by 1821-28 the yearly importation was averaging 9,708 chests. By 1828-35 this average had increased to 18,712 chests and in the years 1838-39 the amount was 40,445 chests. Chinese officials, fearing the effects on their people, had forbidden the importation of opium. Though they did not coin the word "bootlegging" until nearly a century later, yet the practice in opium was as profitable as bootlegging whiskey in the United States during the latter part of the Prohibition era. The Chinese officers, whom they did not bribe enough, would inevitably clash with the foreign merchants. Mr. Lacy suggests that had China only accepted the European nations, much of the opium problems could have been resolved through "diplomatic intercourse."(24) Under these circumstances, men, like Robert Morrison, had to do their missionary activity in secret. Not only were the missionaries in trouble with Chinese authorities, but so were the merchants. The Chinese had troubles of their own because their people and officials were becoming addicted to opium. By 1839 the Chinese sent a viceroy to Canton who "seized and destroyed" some opium and tried to enforce the law. These events simply served to hasten a war, which would entangle both parties. In "June 1840, an English f1eet appeared off Macao and two weeks later captured the island of Chusan, opposite Hangchow Bay... until at length the Chinese, thoroughly beaten, and amazed at the British power, capitulated after the capture of Chinkiang, and accepted the demands of the British."(25) Still, though China lost, they avoided total defeat by giving certain concessions to the British in the Nanking Treaty of 1842. W. A. P. Martyn, a Presbyterian missionary and founder of the Presbyterian Mission in China, concisely summed up the effect of the treaty when he said, "China was not opened: but five gates were set ajar against her will."(26) To summarize what effect that the treaty would have on missions, Mr. K. S. Latourette says, "The cession of the island of Hong Kong to Great Britain, and the opening of foreign trade and the residence of five ports: Canton, Amoy, Foochow, Ningpo, and Shanghai; the inauguration of extraterritoriality; the granting of permission to foreigners to study the Chinese language; a most-favored nation clause; provision for the arrest of foreigners who might attempt to travel outside the ports, and their delivery to the nearest consul; and permission for foreigners to build houses, hospitals, schools and places of worship in the ports then opened."(27) It was at this point that missionaries from all over the world began to arrive in China. As these mission groups came, which were many, they continued to pry the gates that were "set ajar" open. Missionaries from every Protestant denomination arrived in China, all struggling for survival. Around 1895, three mission groups distinguished themselves as the most influential of the missions. These were the American Presbyterians, American Methodists, and the China Inland Mission. "By 1914 the China Inland Mission, had slipped to third place and the two American societies had outstripped it, with the Presbyterians leading."(28) It is the work of the Methodists that will be the main and final focus for the rest of this paper. Methodist missions, with their evangelistic efforts, would become second only to the Presbyterians. Before American Methodism even inaugurated their missionary work in China, they had a split in their own denomination over the issue of slavery. In spite of this fracture, the American Methodist Church moved their evangelistic activities toward China. Owning to the fact that at the turn of the twentieth century this split church reunited, making a designation between them would be useless, except introducing the areas of China in which they labored for the Lord. Beyond this, I will simply call both Northern and Southern Churches the Methodist Church throughout most of this paper. The Methodist Church North chose to send their missionaries to Foochow. They chose this port because it was accessible to the interior. The Methodist Church South chose to start their work in Nanking. It is interesting that "Northern Methodism was facing a southern door, and Southern Methodism was looking toward the most northerly door opened in China. Never again did the Methodist Missionaries look ahead to greater uncertainties and graver responsibilities."(29) For the Northern Methodists, Judson Dwight Collins led the way. Upon his graduation from the University of Michigan, he sent a letter to the Secretary of Missions, saying, "The chief desire of his soul was to carry the gospel to the unsaved in China."(30) In another letter, this time to Bishop James, Collins said, "Secure me a place before the mast, and my own strong arm will pull me to China and support me while there."(31) The burning desire to bring the lost to Christ and a divine call gave Collins a holy enthusiasm to serve his Lord. J. D. Collins was accompanied by Rev, and Mrs. Moses White. They arrived in Foochow in September in 1847. The missionaries were not yet there a year when Mrs. White became ill and died. Some of their hardships mentioned in the journals of the mission were "to acquire a knowledge of the language of everyday life" and "become acquainted with the shape and complexion of their ideas and feelings if we would have our thoughts find entrance and exert influence over them ... "(32) Another problem facing them, was securing Chinese tutors. The fact that no Chinese were converted in the first ten years compounded these impediments. The Southern Methodists, who arrived in Nanking in 1848, were having a few of the same problems. However, they had an advantage because Rev. Charles Taylor had just graduated from the New York University and the Philadelphia College of Medicine. His colleague, Rev. B. Jenkins was "one of the best linguists in the country. With the knowledge of Hebrew, Greek, and Latin, he adds a familiar acquaintance with French, German, and Spanish languages."(33) It is interesting that the Southern Methodist missionaries had the education, medical know how, and the drive to take on China. In contrast, the Northern Methodist lacked in these areas. The Northern Methodists were not met by any friends, and their efforts to find land and buildings helped them to realize that they could not depend on anything in the way of a contract until a bargain was closed. They had still another problem concerning their letters of credit and exchanging them for money. Because of the poor banking system in China, they found it necessary to visit the opium ships, to exchange the letters for Mexican silver dollars. The Northern Methodists felt that this action was responsible for ten years delay before they took into their church the first Chinese converts.(34) The Southern Methodist missionaries had better fortune. Because of his medical knowledge Dr. Taylor had been responding to calls for medical aid as they came to him daily, and Mr. Jenkins said of the Shanghai dialect that "after nearly five months study, I shall need the balance of a year, and good health to continue my labor unabatedly, before I can venture formally into the work." These two missionaries were rewarded for their diligent labors in January 1852 when Liew Tsoh-Sung, a native of Nanking, and his wife, a native of Chang-Chau, were baptized by Jenkins and became the first Chinese Methodist converts. According to Lacy, Liew was an enthusiastic lay preacher after he fearlessly broke with Buddhism to become a Christian. He preached the gospel for almost fourteen years. Liew was twenty-eight years old when he joined the church. Unlike other converts who appeared for a while and fell away, Liew's name kept appearing here and there throughout the history of Chinese Methodism. His zeal to bring people to Christ was better than any other. In the May 1898 edition of the magazine "Review of Missions," he was called a "son of thunder rather than a son of consolation; a voice crying in the wilderness." According to the same magazine, "he died in great peace on the twenty-first of August, 1865."(35) From 1847 to 1857, neither the Northern nor the Southern Methodists saw any great advances. However, both churches witnessed a slow growth. The reason for this slow growth was that this field was unlike mission fields of other countries where the people were poor, ignorant, dirty, and depressed. The Chinese were a proud people, with a desire for scholarly achievements. Since Confucianism seemed to teach the same virtues as Christianity, many Chinese people felt that they did not need to change to the religion of the Westerners. By 1862, the Americans were deeply involved in the Civil War, which also had a negative economic effect on the mission work in China. With these problems, the Methodist missionaries continued to labor faithfully for their Master in China. The Methodists continued to grow. Other Chinese preachers came after Liew: Tang Ni-Lai at Deng-diong, Hu Bo-Mi, Tek Ing-Guang in Fouchow and Kwe Tsang-Iz in Shanghai. These Chinese ministers had a hard time during the Tai-ping Rebellion. Because of their faith in Christ, they were considered traitors by their own people. Still, they continued to build the church. This rebellion could have never stopped these Chinese ministers because of their zeal in their new found religion. Because of the popularity of some of these Chinese preachers, they were admitted into different American Methodist Church Conferences. A good example of this is "Hu Bo-Mi who was admitted into the Wyoming Conference in 1860."(36) In 1869, the Methodist Church in China was sufficiently developed to build an indigenous Chinese leadership. It was in that year that China received a visit from the American Methodist Bishop Calvin Kingsley. A conference was held at Fouchow where the Bishop officially authorized the ordination of four Chinese preachers as both deacons and elders and three as deacons. They called these seven Chinese preachers the "Seven Golden Candlesticks." What is interesting is that the four elders were Confucian scholars (Appendix I & II). It is also interesting how Mrs. Stephen L. Baldwin described these Chinese Methodist ministers in the September 1870 edition of the magazine "Missionary Advocate." She wrote, "Sia became the leading preacher of the Conference and was a delegate to the 1880 General Conference. He refused to take any mission subsidy on his salary, so that non-Christians could not accuse him of preaching for rice. Hu Yong-Mi had already suffered much for his faith, when as pastor of the East Street Church in 1864, a mob had torn down the building, beaten him, insulted his wife and sister, and destroyed all their furniture. His sermons, especially since his ordination, when he seemed to receive a fresh baptism of the Spirit, have been full of power. Lin, the only Hinghwa speaking man of the seven, had been an opium smoker and a partaker in every kind of sin. Bold, eloquent, and full of zeal, yet hasty, impulsive and determined, we have been wont to call him our Peter, as we have termed Hu Yong-rni and Hu Bo-Mi and Sia Sekong our beloved."(37) These men, as one can see, were quiet formidable disciples of Christ. If they were all that this article claims, they would be the finest in China. The other three of the "Seven Candlesticks" were ordained as deacons. They were Li Yu-Mi, "a converted blacksmith, who used to keep his Bible open beside his anvil and studied it between strokes,"(38) Hu Sing-mi, "a younger brother of the two Hus who had already had an opportunity to study in America," and Yeh Ing-guang, "who... had been admitted to the mission boarding school, and after graduation had become a preacher."(39) The "Seven Golden Candlesticks" were just a beginning. Young J. Allen also helped to prompt the burgeoning Methodist Church. In 1881, he opened the Anglo-Chinese College in Shanghai. Mr. Allen also "took a position as teacher and translator for the Chinese government."(40) He felt that one of the best ways to break down the "Chinese attitudes that were barriers to their becoming Christians would be through education."(41) Ding Maing-Ing became the first graduate of the Anglo-Chinese college in 1880. The Methodist Church took a leadership role in China in the field of education. In 1884, the Methodists opened a medical school in connection with Soochow Hospital.(42) In 1888, the Chinese and American Methodists opened a University in Nanking, Nanking University. This university, by 1914, had "seventy-five acres of land, eleven buildings, and thirteen residences."(43) By the turn of the twentieth century, the Methodists had sponsored and built a host of colleges, universities, medica1 schools, and children homes. In 1898, the Chinese Methodist Church was confronted with a political challenge, the Boxer Rebellion. According to Mr. Lacy, "The coup d'´etat came in 1898, when the empress Dawager relegated her nephew-emperor to the role of a nonentity, and assumed drastic control of the empire. It was in this year Mary Robinson wrote of the government school in Chinkiang that its door had closed with a bang "as had many doors throughout the empire which had seemed to be open."(44) It was during this year that Methodism in China gained its first martyr, TangY-Tsi-T. Tang was a "promising medical student" at Chungking who loved his Lord. The young Tang was mobbed at midnight by a raging crowd, "because he had succeeded in renting a house against their wishes."(45) The Boxer Rebellion was not a respecter of any Western influence. Both Protestants and Catholics were in fear of their lives. "On June 20, 1900, an Imperial edict was issued in Peking which called for the slaughter of all foreigners in the Empire."(46) On the day of this edict the North China Conference was just ending and before most of the missionaries and Chinese were able to leave for their homes they were taken from their mission compound and later were turned over to the British legation with the others who were to be exterminated. The siege on the ground or the British legation in Peking lasted for many weeks before they were rescued. After the Boxer Rebellion, the Methodists continued to play an important role in building China, especially in producing leaders in the Chinese political arena. Time would fail to tell in detail of Hsu Wen-Liang and his efforts to rebuild his society and spread the gospel; of T.C. Chao of Yenching University, a loading religious thinker; of Y.C. Yan president of Soochow University.(47) However, the most famous of all the leading Chinese that Methodism produced was Generalissimo Chiang Kai-Shek. Chiang was converted from Buddhism to Christianity under the influence of Mayling Soong, daughter of a Methodist minister, Charles J. Soong, who he later married. Together, Chiang and Madame Chiang Kai-Shek rose in importance in the China political arena. Chiang Kai-Shek became Generalissimo of the Nationalist army and went on to hold many important offices, including a presidency of the Executive Ywan, and twice elected as President of the Republic of China. Madame Chiang Kai-Shek attracted much attention in America for her beauty and courage. Both Generalissimo and Madame Chiang Kai-Shek became Christian influences in the Chinese government, practicing their faith in Christ in the realm of politics. Their influence was felt beyond China through the books they wrote. One of the most famous was Madame Chiang Kai-Shek's little sister, Su Siam, a coup d'´etat. The Kai-Sheks were forced to flee to Taiwan after the communist takeover of mainland China, where they continued their work until his death(48). Chiang Kai-Shek's battle with communism also gave opportunity to spread the Gospel. At one point during this conflict he preached to his soldiers. Many of them responded to the gospel call, giving their lives to Christ. After baptizing(49) a very large group of soldiers, using a hose, the communists attacked, and killed many of them. They are now in eternity with their Lord. Since the fall of China to the communists, apostasy has caused the Methodists to grow cold. Most United Methodist missionaries are more concerned with "social justice" and well being. Even the Wesleyan Holiness movement has grown cool to preaching the Gospel of Christ. They would find it easier to preach holiness as a greater need then salvation in Christ. Wesley himself preached to win souls to Christ. This was his burning passion and that of his followers. What mainline conservative Methodist groups are left have long forgotten their Methodist Arminian heritage thus causing them to look more Baptist or Calvinist then Methodist. The doors again have been "set ajar" to China. To our surprise we found that the Church of our Lord had grown even under communism. Bible believing Methodism now has another opportunity to enter both China and Russia. Pray that God would use Methodism again to preach His Gospel to all the world. What Bible believing Methodist would go, even if he had to use his two strong arms to get there as, Collins announced more than 150 years ago? According to the official Methodist church records, four of the Chinese preachers of the "Seven Golden Candlesticks," Sia Sek-Ong, Hu Yong-Mi Hu Bo-Mi and Tin Ching-Ting, were Confucian scholars. Mr. Lacy however, does not acknowledge these four men as Confucian scholars anywhere in his book. Even the description given by Mrs. Stephen Baldwin left out any idea that these four men were Confucian scholars. The nearest that any of the four men came to being a Confucian scholar was Sia Sek-Ong who "was a literary Man." After having this sketch of Methodist History in China on line for over a year, I received this interesting letter for a reader in Arizona. I was thrilled to have received this information. With their permission I am adding this as an appendix. I am sure that you will enjoy this as much as I did. I want to thank Dr. Christopher C. May for taking time to add this wonderful dimension to this article. Concerning the Seven Golden Candlesticks I would like to direct your attention to a book called 'Nathan Sites: An Epic of the East', published in 1912 by Revell. This book is a record of the mission served in Foochow by my great-great-grandfather, Rev. Nathan Sites of Ohio. He was a graduate of Ohio Wesleyan and was a missionary to the Chinese from 1861 until his death in Foochow in 1895. The book is taken from his journals, edited and addended by his wife, Sarah Moore Sites, who accompanied him to China. Dr. Sites is the missionary who converted Sia Sek Ong. Mrs. Sites describes him thus: "In one of these excursions [Rev. Sites] came to a village where lived a young teacher of whom he had already heard... On set days he led his pupils in performing prostrations before the tablet of the Great Sage. There was something in this teacher's bearing, however, which showed that he was not mastered by his circumstances; one might guess that Buddha's answer to the riddle of life was not satisfying to him.... There was a return visit, then an interchange of polite tokens, in consequence of which the Confucianist found himself the possessor of an attractive book... telling of a Greater than Confucius... We lacked a good teacher for the Chinese classics; we invited the Confucianist, and he accepted.... I recall the embarrassment which I felt when I conducted morning prayers, in my imperfect Chinese, in the presence of the Confucian scholar... Well do I remember the joy of the Sunday evening a few weeks later, when Mr. Sites, returning from a quarterly meeting, told me he had that day baptized, with others, our Confucian teacher. This man was Sia Sek Ong." The brothers Hu are described as being "of a high literary family" and in that time and place that would certainly imply study of the Confucian classics. I have enclosed a photograph of Sia Sek Ong from the book, attached to this e-mail message. Yours in Christ, Christopher C. May, M.D. Arizona

BIBLIOGRAPHY Barnrn, Pete, The of Christ, New York: McGraw Hill Book Co., Inc, 1959. Chia, Earl N., lecture notes Harmon, Nolan B., editor, Encyclopedia of World Methodism, Vol I & II, Nashville; United Methodist Publishing House, 1974. James, Willis, A History of the Expansion of Christianity, Vol VI, A.D. 1800 A.D. 1914, New York Harper & Brothers Publishers., 1944. Lacy, Walter N., A Hundred Years of China Methodism, Nashville Abingdon-Cokesbury Press, 1964 Macauley, Samuel, Schaff-Herzos Religious Encyclopedia, Vol III, Grand Rapids: Baker Book House, 1959. Mayer, Elgin S., Who Was Who in Church History - revised, Chicago: Moody Press, 1962. Watson, Richard, A Biblical and Theological Dictionary, New York: B. Waugh & T . Mason, 1832. World Book Encyclopedia, Vol IV, Chicago, Field Enterprise Educational Corp., 1964. 1. Watson, Richard, A Biblical and Theological Dictionary, New York, B. Waught & T. Mason, 1832, p. 700 2. Bamm, Pete, The Kingdom of Christ, New York, McGraw Hill Book Co., Inc. 1959. p. 228 3. Ibid., p. 229 4. Ibid., p. 230 5. Ibid., p. 228 6. It should be noted that Peking was the name of the capital of China during the time period that this survey covers. However, in recent years the name of Peking has be changed to Beijing. 7. Ibid., p. 233 8. Moyer, Elgin S., Who Was Who in China History, Chicago, Moody Press, 1963, p. 349 9. Ibid., p. 349 10. Ibid., p. 349 11. Ibid., p. 349 12. Chia, Earl N., History of China, Lecture notes 13. World Book Encyclopedia, Volume 4, Chicago, Field Enterprise Educational Corp., 1964. p. 276 14. Macauley, Samuel, Schaff-Herzos Religious Encyclopedia, Volume 2, Grand Rapids, Baker Book House, 1959, p. 3 15. Ibid., p. 3 16. World Book Encyclopedia, op. cit., p. 276 17. Matthew 7:12 It is here where our Lord teaches us the Golden Rule. He says, "Therefore all things whatsoever ye would that men should do to you, do ye even so to them: for this is the law and the prophets." 18. Macauley, op. cit., pp293-294 19. Ibid., p. 294 20. Chia, op. cit. 21. Moyer, op. cit., p. 293 22. Ibid., p. 293 23. Lacy, Walter N., A Hundred Years of China Methodism, Nashville, Abingdon-Cokesbury Press, 1964. pp.24-25 24. Ibid., p. 24 25. Ibid., p. 24 26. Ibid., p. 25 27. Ibid., p. 30 28. James, Willis. A History of the Expansion of Christianity, Volume 3, New York, Harper & Brothers Publishers, 1944. p. 341 29. Lacy, op., cit., p. 24 30. Ibid., p. 25 31. Harmon, Nolan B. ed, Encyclopedia of World Methodism, Nashville, United Methodist Publishing House, 1974. p. 543 32. Lacy, op., cit., p. 31 33. Lacy, op., cit., p. 35 34. Ibid., p. 43 35. Ibid., p. 297-298 36. Ibid., p. 309 37. Harmon, op., cit., p. 2126 38. Ibid., p. 2126 39. Ibid., p. 2126 40. Ibid., p. 91 41. Ibid., p. 91 42. Lacy, op., cit., p. 311 43. Ibid., p. 161 44. Ibid., pp. 120-121 45. Ibid., p. 131 46. Ibid., p 121 47. Ibid., p. 269 48. Harmon, op., cit., pp 465- 466 49. Mjorud, Herbert, What's Baptism all About?, Carol Stream, Illinois, Creation

House, 1978. p. 63. According to Mr. Mjorud, "there was no time for individual

baptisms. The communists were attacking and the defenders were in imminent

danger. Therefore he took a water hose and baptized them all at the same time in

'the name of the Father, the Son, and the Holy Ghost'." We see how

impractical immersion would have been.

This certainly was a case of being baptized

in the spirit and meaning of the mode as

discussed, taught, and practiced in the New Testament.

Immersion is a practice in dogmatics and "conviction", and

not the practice of Christ, his followers, and scripture.

Pastor Hartman has been in the ministry for twenty six years. He graduated from the Institute of Christian Service of Bob Jones University. He also holds a B.S. and a M.S degree from Columbus State University. His has traveled once to Russia, three times to the Ukraine, twice to England in a humble effort to help the missionaries spread the Gospel of Christ. It is his hope and prayer that some day China would enjoy the freedom to hear and preach the gospel of Christ. If you would like to contact Pastor Hartman, please feel free to do so. |